It is no secret that the most internationally acclaimed directors from Japan are men: Akira Kurosawa, Yasujirō Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi, Takeshi Kitano, Hayao Miyazaki, Takashi Miike, Hirokazu Koreeda and so on. A seemingly inexhaustible list. For women in Japan’s socially conservative film industry real equality is still far away.

Looking at female Japanese directors, I will in this exhibition show how the situation of women in this country is about to change. The focus will be on two directors from just before and just after World War II and on three directors of our own time who have made their marks in a male-dominated industry in a still gendered Japanese society.

Tazuko Sakane (坂根田鶴子, 1904-1975) is regarded as Japan’s first female director. Sakane cut her hair short and dressed in men’s clothing to fit into the male-dominated profession, and got the chance to make the film New Clothing (初姿) in 1936 after the legendary director Kenji Mizoguchi took her under his wing. It was to be Sakane’s only feature film; the film flopped and Sakane never got the opportunity to direct a feature film again. But Sakane was also one of the world’s first female documentary filmmakers and during Japan’s invasion of Manchuria (a large area in Northeast China), she made documentaries and propaganda films from that area. One of these, Pioneer Bride/Brides on the Frontier (開拓の花嫁) from 1943, is about a young wife who strives on an equal footing with men in Manchuria while she raises a family. The film follows the recipe for national political films, but it also puts cooperation between the sexes as a prerequisite for intercultural cooperation. When the war ended, Sakane was banned from her profession as a director and had to start all over again from scratch in the hierarchy of the film industry as an “assistant” at the age of 42. After Sakane there were no more films made by women in Japan until after WWII, when Kinuyo Tanaka entered as Sakane’s successor. A beginning sense of acceptance of female filmmakers in Japan was not evident until much later.

Kinuyo Tanaka (田中絹代, 1909-1977) followed Sakane as Japan’s second female director. She is most famous for her acting and her career lasted over 50 years with more than 250 credited films. Tanaka is famous for her roles in the films of directors Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujirō Ozu where she excelled in roles defined by a restrictive patriarchal perspective. As a director, however, Tanaka showed a more individual and feminist side. Unfortunately, in the 1950s a discriminatory society did a good job to remove women from all leadership positions in the Japanese film industry. In this misogynist environment it is really amazing that Tanaka was allowed to direct films at all. Her first director job was with the romantic melodrama Love Letter (恋文) in 1953 which was shown at the Cannes Film Festival in 1954. The film is in the shomin-geki genre which traditionally portrays the lives of ordinary Japanese people. Tanaka also directed films such as The Moon has risen (月は上りぬ) in 1955 and Wandering Princess (流転の王妃) in 1960. The Moon has risen is a melodrama with clear feminist themes. It is about the commitment of three sisters and the youngest sister refuses to accept the strict, enforced social codes for how Japanese women are expected to behave.

Naomi Kawase (河瀨直美, 1969-) began her career making short documentaries and experimental films. With interest in the autobiographical, most of Kawase’s early films focused on her own turbulent childhood and family history. Kawase grew up in rural Nara and the countryside has been a great source of inspiration for her films. Her parents divorced early in her childhood, leaving her to be raised by her aunt. Kawase’s films are poetic and vivid and raises questions about nature, family and human existence. In addition to being a director she is also a film producer and she is the founder and director of Nara International Film Festival. Several of Kawase’s films have won prestigious awards at film festivals and she has consistently made her mark with her bold and self-reflexive cinematic style. In 1997, her film Suzaku (萌の朱雀) gave her the distinction of being the youngest person ever to have been awarded the prestigious award Camera D’Or (best new director) at Cannes Film Festival. The Mourning Forest (殯の森) won the prestigious Grand Prix during Cannes in 2007 and tells the story of a nurse who mourns over her dead child. She works in a nursing home and gets a special relationship with an older man with dementia who searches the local forest for something related to his dead wife that he cannot explain.

Naoko Ogigami (荻上直子, 1972-) studied and worked with film and film production for six years in the US before she moved back to Japan in 2000 and began writing screenplays and directing films, in addition to starting her own production company in 2008. Ogigami’s feature film debut was with Barber Yoshino (バーバー吉野) in 2004. Since then her films have been shown at numerous festivals worldwide. The plot in the comedy Kamome diner/Seagull diner (か も め 食堂) from 2006 is placed in the Finnish capital Helsinki and is about a Japanese woman who opens a cafe that serves Japanese food, and the friends she gets. Ogigami is probably most famous here in Norway for Glasses (めがね) from 2007. The film screened in Norwegian cinemas in 2009 and it tells the story of a university professor who is vacationing on an unnamed Japanese island, where she comes in contact with several eccentric local inhabitants. In Ogigami’s sixth feature film Rent-a-cat (レンタネコ) from 2012, the protagonist rents out cats as company to lonely people. It was nominated for Best Feature Film during the Films From the South festival in Oslo.

Miwa Nishikawa (西川美和, 1974-) is a writer and director and is one of the most acclaimed names in the Japanese film industry today. Nishikawa began her career working with several independent films in addition to being discovered by director Hirokazu Koreeda. The breakthrough as a director came in 2003 with her first feature film Wild Berries (蛇イチゴ) in collaboration with Koreeda. Since then her films have been met with enthusiastic critical acclaim in Japan. Sway (ゆれる) from 2006 was a huge commercial success and was the only Japanese film to compete for the prestigious Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Many of the most acclaimed filmmakers in Japanese film history are those who center their films in the everyday sphere. From world-renowned classic names like Yasujirō Ozu and Mikio Naruse to names like Hirokazu Koreeda from our own time. The same can be said about Miwa Nishikawa. As an example, Wild Berries has a classic generation-gap theme between parents and children, while Sway explores the strained relationship between two brothers, one of which stayed in the village where they grew up, while the other escaped to the city as fast as he could. Nishikawa stands out by having a special approach to her narratives; namely to involve one or more of the main characters in often serious crimes. By crossing everyday chores with crime, her films are ultimately concerned with the subjective nature of morality.

Poster

Exhibition parts

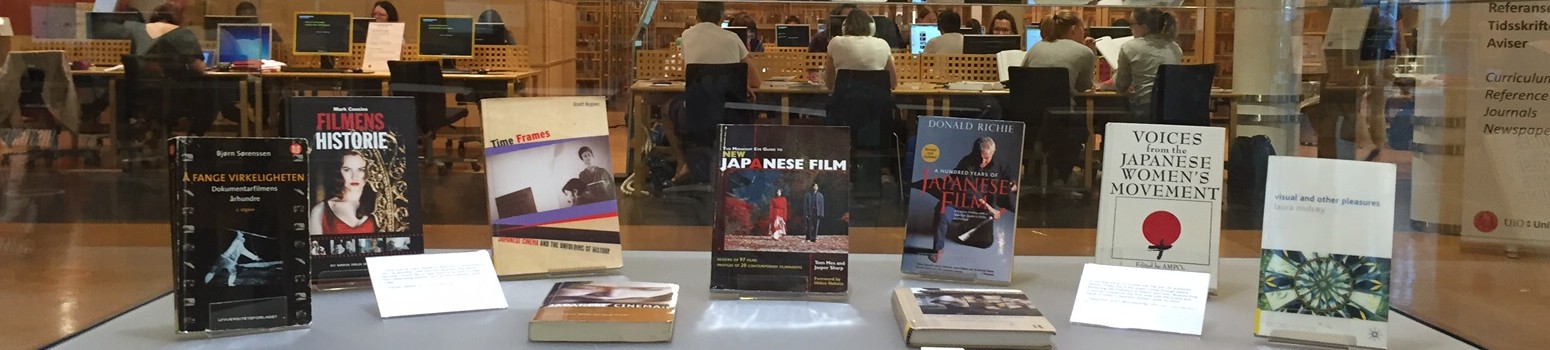

See also

E-book

Nelmes, J., & Selbo, J. (2015). Women Screenwriters : An International Guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Book

Yamamuro, S., & Fogel, J. (2006). Manchuria under Japanese dominion (Encounters with Asia). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Other resources

Library search

Search in Oria with subject

- Film + Japan

- Women + Japan

- Director + women

.jpg)